|

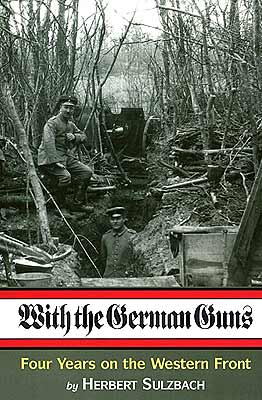

Herbert Sulzbach was born in Germany in 1894.

He volunteered for the German Army in 1914 and served until

1918. He kept a diary during the First World War and this

was published as With the German Guns, Fifty Months on the

Western Front, 1914-1918 in 1935.

Herbert Sulzbach was an interesting guy. Joining the German

artillery at the beginning of World War I, Sulzbach fought

through the entire war without a scratch, in the process winning

two Iron Crosses. After the war, after fleeing the Nazis and

emigrating to England, Sulzbach joined the British army, ultimately

being commissioned as an officer during WW II. Following his

second world war with his second army, Sulzbach returned to

Germany, where he worked for the rest of his career as a cultural

officer for the German government, eventually being awarded

the Paix de l'Europe medal for the promotion of cross-cultural

understanding. Sulzbach was a notable man living in notable

times. However, it was with the 1935 publication of his Great

War memoirs, With the German Guns, that Sulzbach first gained

his notoriety.

This intimacy is both the book's main strength, and its weakness.

It is hard not to like Sulzbach. His writing style is fluid,

and observations are both touching and personal. The intense

intimacy creates a bubble dividing Sulzbach, and the reader,

from the big picture.

|

|

|

He was born February, 1894, into a wealthy and respected

Jewish family of Frankfurt-on-Main. His grandfather, Rudolf,

was the founder in 1855 of the Sulzbach private bank (Bankhaus

Gebruder Sulzbach), one of the founders of the Deutsche Bank-today

one of the 'Big Three' German commercial banks-as well as

a partner in a number of other major industrial undertakings.

He was offered a title of nobility by Kaiser Wilhelm II, but

refused it. Herbert's father, Emil, inherited the family business

which was recently taken over by the banking firm of Oppenheim.

He died in 1932, on the eve of the Nazi seizure of power.

Frankfurt named a street 'Emil Sulzbach-Strabe' in gratitude

for his contribution to Frankfurt's cultural life.

Herbert Sulzbach volunteered for military service at the

outbreak of the war in 1914 and was accepted in the 63rd (Frankfurt)

Field Artillery Regiment on 8 August. Four weeks later he

was on his way to the Western Front. He was to stay there,

but for one short spell of service against the Russians, for

the next four years.

He won the Iron Cross, second class, in the Battle of the

Somme in 1916, and the Iron Cross, first class, after the

bloody Battle of Villers-Cotterets in 1918. He received the

'Front-Kampfer Ehrenkreuz' (Front-line Cross of Merit) from

Field-Marshall Paul von Hindenburg, later to become President

of the 1919-33 Weimar Republic. Among his war-mementoes is

a letter from Field-Marshall Ludendorf, with photograph, thanking

him for his zeal in discovering the wreckage of his dead stepson's

aero plane. Years later, in 1935, his own wartime diaries

were published under the title of 'Zwei lebende Mauern' (Two

Living Walls). The book received enthusiastic reviews, even

from Nazi newspapers and journals-whose editors must surely

have been unaware that the author came from a Jewish family

and therefore a supposed and proclaimed enemy of the German

race. The Berlin publishers, Bernard and Graefe, included

"Two Living Walls" in a prospectus of three specially

recommended books. Ironically the other two were profusely

illustrated short biographies of Hitler and Mussolini.

Two years after his book was published, Herbert Sulzbach

had to leave Germany. Nazi persecution of the Jews was already

under way, and it would have been dangerous, even suicidal,

for him to have stayed on...

He had to leave, and he chose to go to Britain. One reason-in

spite of having fought for four years against the British,

he had an admiration and even a feeling of affection for them

and their country. And, a more mundane consideration, he had

built up a firm in a Berlin suburb, making fancy paper for

box coverings and book bindings and doing a busy trade with

Britain. A Branch of the firm was opened in Slough, offering

at least a chance of a living.

In 1938 he returned to Berlin to fetch his wife Beate, niece

of Prof Otto Klemperer, the great conductor, and her sister-a

highly risky undertaking. At Bremerhaven, where he landed,

he had to stand waiting while a passport official checked

his name against the list held below desk-level, but found

nothing. He brought the two women, both Jewish, safely to

Britain but to a life which was to be far from easy. First,

the Slough branch of his firm failed. He was deprived of his

German nationality by Nazi decree, thus becoming stateless,

and was unable to recover assets left in Germany. Then, with

the outbreak of the Second World War, he became, technically,

an enemy alien. He and his wife had to leave their home in

North London and were interned on the Isle of Man-in spite

of his having volunteered for service in the British Army.

Life on the Isle of Man, with Nazis and anti-Nazis gathered

in together, must have been nightmarish. Perhaps the only

fortunate circumstances was that neither Herbert nor Beate

was in their home when it was flattened by a Luftwaffe bomb

during a raid in November, 1940...

|

Just before this, Herbert Sulzbach had in fact been accepted

for military service; his desperate efforts to volunteer had

at least been taken at face value.

He joined the Pioneer Corps

as a private and spent much of the next four years building

defenses against possible German landings from sea or air-a

strange contrast indeed to his four years of fighting on the

Western Front from 1914 to 1918! As the chances of German

landings became ever more remote, his work became increasingly

unrewarding.

With ever large numbers of Germans being taken

prisoner-of-war, he decided to offer his services as an interpreter;

and at the end of 1944 he was transferred to the "Interpreters

Pool" and posted as a staff sergeant to Comrie P.O.W.

camp in Scotland in January, 1945...

He made it his business to talk and reason with the 4000

men in his charge. Many of them were red-hot Nazis; quite

a few were members of the Nazi fighting-elite, the 'Waffen

S.S.', an organization proscribed as criminal by the Nuremberg

War-Crime Tribunal after the war.

The task which he undertook

was daunting; he discharged it with immense and infectious

enthusiasm, with great patience and with an absolute belief

in the virtues of the democratic way of life which he made

it his duty to explain.

His success was aptly illustrated

by what took place on Armistice Day, November 11, 1945...earlier

he explained to the German prisoners the meaning of 'poppy

day', read them John McCrae's poem In Flanders Fields, and

proposed in these words how they should celebrate the occasion:

"If you agree with my proposal, parade on November 11

on your parade ground and salute the dead of all nations-your

comrades, your former enemies, all murdered fighters for freedom

who laid down their lives in German concentration-camps-and

make the following vow; 'Never again shall such murder take

place! It is the last time we will allow ourselves to be deceived

and betrayed. It is not true that we Germans are a superior

race; we have no right to believe that we are better than

others. We are all equal before God, whatever our race or

religion. Endless misery has come to us, and we have realized

where arrogance leads...In this minute of silence, at 11 a.m.

on this November 11, 1945, we swear to return to Germany as

good Europeans, and to take part as long as we live in the

reconciliation of all people and the maintenance of peace..."

Out of the 4,000 German P.O.W.'s only about a dozen stayed,

like Ajax, sulking in their huts. On a raw November morning

the remainder stood to attention on the football field, while

the 'Last Post" was played. Herbert Sulzbach's own comment:

"Nazism could be fought and beaten as early as 1945."...

To his Iron Crosses of the First World War, Herbert Sulzbach

has added the German Cross of Merit 1st class and recently,

the Grand Cross of the German Order of Merit to wear alongside

his British medals of the Second World War. Granted British

citizenship in 1947, he was given back German nationality,

filched from him by Hitler, in 1952. For the last two decades

he has had two 'fatherlands' and his love of both has reinforced

his belief in the future of Europe.

The man who has worn both

khaki and field-grey has come a long way; his war diaries

are a major episode on a road which he has trod with great

good humor and honest courage.

Terence Prittie

September, 1972

|